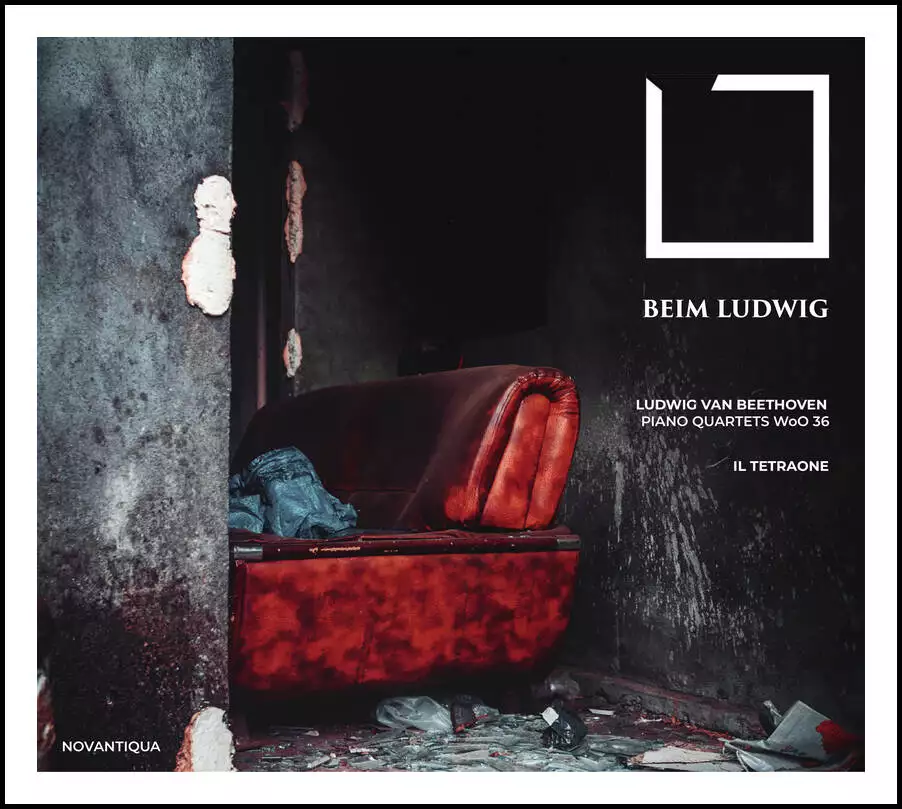

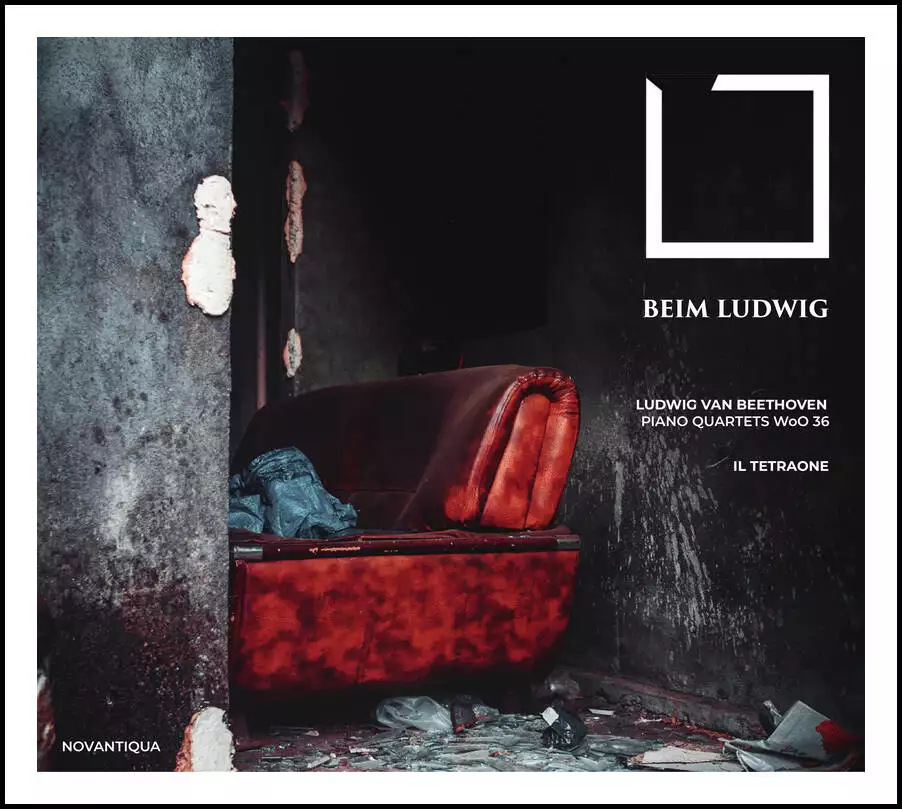

Beim Ludwig

Il Tetraone

Beim Ludwig

Tracklist

-

1. Beethoven | 3 Piano Quartets WoO36 | Il Tetraone

Il Tetraone, piano quartet on period instruments with Beethoven Piano Quartets. A very young Beethoven composed these quartets as teenager, but a Genius is a Genius and these three Quartets already have the quality and the energy of the well known Ludwig!

IL TETRAONE: Ana Liz Ojeda, violin – Alice Bisanti, viola – Paolo Ballanti, cello Valeria Montanari, fortepiano – Novantiqua LC 28904 - NA93

Available on Novantiqua Records

°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°

CD REVIEW

IL TETRAONE: LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN PIANO QUARTETS Wo036

This is the third recording by the quartet "Il Tetraone." To be precise, the CD was released some time ago, but this appears to be its first review.

In times past, placing the turntable arm onto the opening groove of an LP might have sent a thrill down one's spine. Personally, I have a preference for the small digital medium, which, in my view, completely negates any claims of analog sound’s superiority—claims often made by those seemingly unable to sever an increasingly frayed umbilical cord to the past.

With this warm welcome to a 15-year-old Beethoven, Il Tetraone establishes both continuity with its previous album, TRAZOM HAUSMUSIK, and a psychological contrast to it. The continuity can be found in the interpretative approach, which is hinted at even in the album titles. While TRAZOM HAUSMUSIK laid bare the possible need to rethink Mozart's image—one that has often been shaped by instruments no longer suited for domestic settings—BEIM LUDWIG instead suggests a loving reception of a young composer's earliest works. Here, there are no barriers, no attempts to foreshadow the future known only to posterity; instead, the music paints a world in its purest form, much like love in its nascent state.

One immediately realizes that these are not masterpieces, yet neither are they mere experiments devoid of interest. Beethoven was not Mozart, nor Schubert, nor Mendelssohn—composers who, by the age of fifteen, had already provided clear evidence of their genius and left significant clues about their future musical directions. Beethoven remained simply Ludwig for many years, as long as it took for him to initiate the revolution that would pave the way for Romanticism. Only with the arrival of the new century would he make the unimaginable leap that distanced him from his youthful years—so much so that he disregarded these early works entirely, leaving the Wo036 quartets out of his own catalog.

Il Tetraone approaches these pieces with both technical and interpretative freedom, placing itself in an imaginary time and space that is unaware of what the future holds. We are inside a film where a young Ludwig is attempting "to impress and astonish his audience by referencing the dominant Mozartian model." The interpretative intent is to align with that youthful spirit, and that is exactly what happens—or at least, that is the impression conveyed. Il Tetraone approaches the three quartets without the weight of hindsight, treating them purely as the work of Beethoven at that age—without excessive analytical overlays or retrospective comparisons. The listener, in turn, unconsciously aligns with this approach, which might seem obvious or even taken for granted. However, in reality, it is difficult to erase the ever-present image of the man who, more than any other, came to symbolize "fate knocking at the door." This creates a twofold risk: on one hand, of equating these youthful experiments with Beethoven’s mature masterpieces, or, on the other, of dismissing them entirely—much like Beethoven himself, who never included these quartets in his catalog.

Rather than forcing a direct comparison with Mozart’s two piano quartets, KV 478 and KV 493— which were written around the same time as Beethoven’s Wo036 quartets—I prefer to trace even the faintest hints of the future Beethoven within young Ludwig’s music, while avoiding the pitfalls I mentioned earlier. Based on the recording order of the quartets, the ones in C major and E-flat major felt closer to the Beethoven we recognize, whereas the final quartet, in D major, seemed more rooted in its own era—more distinctly 18th-century in style. In the first two quartets, one can perceive faint dramatic accents in some of the strings’ sforzandi or a greater poignancy in the fortepiano’s interaction with the strings. The third quartet, in contrast, strikes me as more serene, more naturally anchored in its specific historical moment.

Regardless, the emotional journey remains ever-present—indeed, it is central, as it should always be in music. The beauty of the sound plays a crucial role in enriching that emotion. The digital medium, far from being mechanical or sterile, enhances the clarity and crystalline, yet never aggressive, sound captured in BEIM LUDWIG.

Enzo Vignoli

March 5, 2025